FROM THE RESEARCH CORNER

Johne’s Disease: Is it Stealing Milk from Your Vat

By: John Spearpoint

With the New Year behind us, your mind is likely on mating results and maximising production through the remainder of the season. While we’re focused on pregnancy scanning, SCC, and milk persistence, there is a "silent passenger" in many New Zealand herds that deserves a look. Johne’s disease (JD) is a chronic bacterial infection that often looks like simple ill-thrift but acts as a major profit drain long before a cow shows signs of wasting.

Here is a Q&A to answer some of the common questions we often get asked about Johnes disease.

Q: My cows look healthy and in good condition. Should I worry about Johne’s?

Johne’s is often called the ‘skinny-hungry’ cow disease. It’s a slow-burn disease, having a long incubation period (typically 4–6 years), meaning a cow can be infected for years while looking perfectly healthy. While you may have a few cows that just don’t seem to perform, this could be the ‘iceberg effect’: for every cow you see with clinical symptoms, there are likely 25 others in your herd already infected and spreading the bacteria. These hidden cases cost you through:

15% Less Milk: High-positive cows produce significantly less milk solids than their healthy herd mates. Across the New Zealand dairy industry, Johne’s is estimated to cost farmers between $40 million and $80 million every year.

Inefficient Feed Conversion: Think of it like a tractor with a partially blocked fuel filter. She still runs, but she lacks power under load and burns more "fuel" (feed) just to keep up, until one day she stops altogether.

Reduced Fertility: Infected cows are often your ‘repeat offenders’ who take longer to get back in calf.

VET’S TIP: Annual Johnes milk testing is the only way to find which ‘tractors’ (cows) need to be traded in before they break down completely.

Q: I just got my Johne’s milk test results. What should I do with "High Positive" cows?

These are your super-shedders, pumping out millions of bacteria in their dung. Your priority is to remove them from the environment as they are contributing towards persistence of Johnes in your herd.

Cull ASAP: Best practice is to remove these cows immediately, and definitely before they calve. If you allow them to calve, they will heavily contaminate your springer paddocks and calving environment, putting your next generation of calves at extreme risk.

Confirm Suspects: Approximately 78% of cows with "Suspect" milk results are found to be positive on follow-up blood tests. Confirm their status before making a final culling decision.

Protect the Next Generation: Never keep replacements from a JD-positive cow, and do not feed colostrum or milk from a Johnes infected cow to any calves.

VET’S TIP: A negative test doesn’t mean she’s clear of Johnes disease. Annual testing is important to pick up infected cows that move from being low-risk to high-risk.

Q: Why doesn’t ‘test and cull’ immediately eliminate the disease?

Breaking the Johne's cycle takes several seasons of consistent effort.

The Long “Waiting Room”: Younger cows often have the disease but aren't yet producing enough antibodies to be detected. Current diagnostic tests are great at finding cows in the advanced stages disease, but they often miss cows in the early stages.

Environmental Survival: Johne’s bacteria are robust and can survive for up to 18 months in effluent-sprayed paddocks or shaded pastures.

The "Top-Up" from replacements: Replacement calves exposed to infected faeces &/or milk have swallowed enough bacteria from the super-shedders to become the next generation of sick cows.

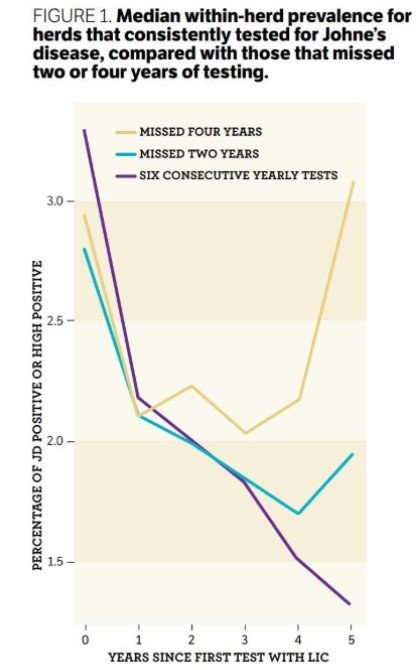

VET’S TIP: Consistency is Key: LIC data shows herds that skip annual testing see prevalence rebound, resulting in a loss of the initial investment in testing. Consistent culling allows the disease to "age out" of the herd while you prevent new infections.

(Image courtesy of NZVA VetScript and LIC)

Q: When is the best time to test?

Most Johnes milk testing occurs between January and May. This allows for a clear culling plan before the stress of drying off and calving.

Because calving is such a strong trigger, any positive cows should be culled before they calve. This saves you the cost of wintering a cow that is likely to die or "crash" during calving and prevents these super-shedders from dumping millions of bacteria onto your calving pad, where your most vulnerable new calves will be born.

VET’S TIPS: Demand for Johnes milk testing has been strong this season. If you would like to book a Johnes test, we recommend you book this in now via your primary vet.

New booking process: Next season, all Johnes disease bookings will automatically roll over each year. This means herds booked in the previous season will be rebooked for the same time slot in the new season. This new process allows LIC to prioritise bookings for existing customers and helps secure preferred testing dates earlier in the season.

Important: Ensure a 43-day gap for milk testing (or 71 days for blood) after any Bovine TB testing to avoid false results.

Q. I need to carryover some Johnes positive cows into next season to keep herd numbers up?

Understandably keeping herd numbers up to keep the vat full seems sensible. But, this is like trying to save a sinking boat by keeping the heaviest rocks on board.

• Prioritise for Culling: If you can’t cull them all immediately, put them at the top of your culling list. If you must carryover Johnes positive cows, identify and monitor these cows.

• Manage the Calf: Don’t rear heifer calves from these cows as replacements.

• Monitor for the Clinical “Crash”: Positive Johnes cows have a higher risk of dying on farm. Calving is the ultimate "stress test" for a cow’s body and often becomes the trigger that causes the disease to progress from a hidden (subclinical) infection to a visible (clinical) one. Once triggered, the disease moves into its final stage. The gut wall thickens so much that the cow can no longer absorb nutrients, leading to signs of profuse diarrhoea, muscle wasting, and weight loss, despite having a normal appetite.

VET’S TIP: Infected cows are like a truck with a badly frayed fan belt. It might look and run fine while it’s idling in the driveway (subclinical), but as soon as you put it under load on a steep hill (calving or lactation), that belt is going to snap. You’re not going to know when the belt snaps and you’re likely to end up with a cow that’s only suitable for pet food rather than realising some salvage value.

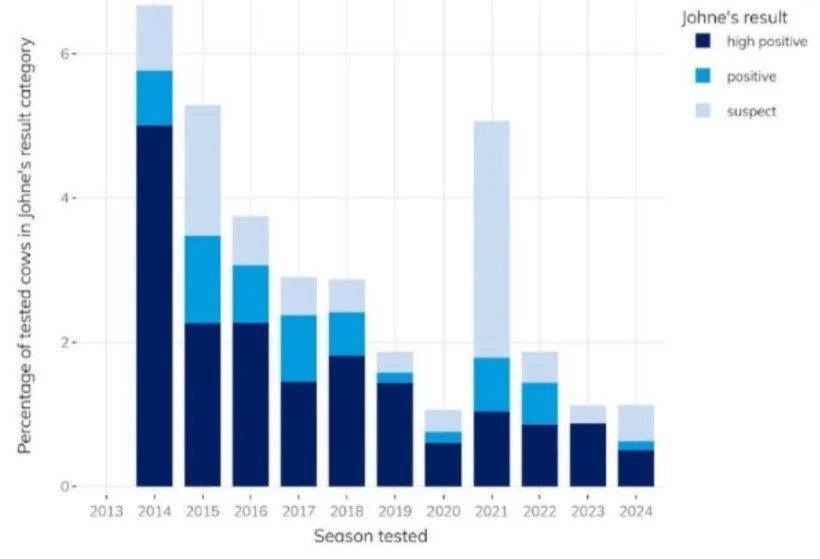

New developments – LIC Johnes Dashboard

Over the past couple of seasons, we’ve been working with LIC testing a prototype Johnes Dashboard. This enhanced reporting tool is designed to track Johnes disease trends, identify high risk cows and support better management decisions on farm.

Feedback from some of our focus farms, who have been Johnes testing for more than 5 years, found this dashboard useful and improved their understanding of Johnes management. Our testing has helped inform changes and new enhancements in the dashboard. Further testing will occur this season, and it is hoped it will become available in MINDA next season.

Tracking over time: Graphs allow you to track prevalence of Johnes on your farm over time and identify ‘at risk’ animals.

Daughter Tracking: If a cow is high-risk, her daughters are also at higher risk. The dashboard helps us flag these replacements so you can decide if they are worth keeping in the long term.

It Finds the "Problem Years": Because Johne’s is a "slow-burn" disease, the dashboard uses cohort analysis to show you which specific age groups are most at risk.

Benchmarks Your Progress: Comparing your herd’s performance over time and against the national/regional averages gives feedback on progress and helps you decide whether additional strategies should be considered.

THE BOTTOM LINE: Managing Johne’s is a marathon, not a sprint. The decisions you make this season will shape your Johnes situation in eight to ten years from now.